☆ 025 ; reflections: the shifting image

For the foundations unit, I started with a basic definition of “the shifting image”, a key phrase from Kevin Lynch’s book Image of the City. This phrase refers to the idea that an object [whether it be a building, space, artifact, or place] is a series of images that overlap and interrelate to create a sense of being in a user’s mind. For the alternatives unit I added on a layer describing imageability, or the perceptual experience describing how we receive, interpret, and store information that we come into contact with through our senses. As we arrive at the end of the reflections unit, I want to build upon this definition of “the shifting image” by introducing the idea of element interrelations.

The elements that Lynch refer to in his book include paths, edges, districts, and nodes, which describe his city image, but I think can be connected to the world of architecture and the objects people produce, or at least new elements can be invented to illustrate the same sorts of ideas. Lynch defines each element, but then goes on to highlight the importance of the relations between unlike elements, as “such pairs may reinforce one another, resonate so that they enhance each other’s power; or they may conflict and destroy themselves” (pp. 83-84). In other words, there are concrete and abstract relations between elements that shape the image and thus the experience we have of the object. This idea is key throughout the aspects [nature, people, material, symbol], and I will go into greater depth below.

For my purposes, defining a new set of elements would be more apt for the type of objects I will be looking at. I think forms, faces, scales, and ornamentation best describe the sorts of interactions the built environment has with the aspects.

NATURE

The reflections time period is seeing a great shift from rural living to urban living, due to the Industrial Revolution, which shifts a nation’s economy from a primary, or agricultural economy, to a secondary, or industrial economy. There is a huge influx of people into cities, most notably in Europe and America. The key city in the United States at the time was Chicago, which saw a rise in population from 300 in 1833 to 2 million in 1900, even surpassing the population of New York City. Accordingly, as urban areas become dense, the environmental context loses out on a natural site aspect and adopts an architectural site aspect. Chicago demonstrates this idea the best, especially after the Great Fire of 1871, which destroyed an area of Chicago four miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide. With a clean slate, so to speak, and driven by other factors, like higher rates of land price, the advent of a safe elevator, and iron skeletal construction, innovators flocked to Chicago to begin to rebuild. Here we see the birth of the skyscraper.

The skyscraper is important in the development of the American city as it reorganizes the urban center, and in this way the natural site aspect disappears and is replaced by “the concrete jungle”.

The Reliance Building best exemplifies this movement into the urban environment, and its implications are vast and far-reaching. It is a Chicago hallmark, designed with Burnham and Root and constructed between 1883 and 1885. In terms of form, the basic unit that was already defined as the form for the skyscraper is modified; the form is still blocky and heavy, but a geometric undulation is introduced to help break up the space and create more faces. The faces, or the façade, is fluid, and because of careful application of scales and ornamentation we can better understand the relation of the forms to the aspects. There is a strong horizontal feeling, as similar segments are banded together across the faces [windows, ornamented spandrels], which are clearly marked and scaled. It gives us a sense of movement upwards, and the top of the skyscraper stops our eye, like a period at the end of a sentence.

Robie House acts as an interesting foil to the Reliance Building. Another Chicago landmark, Robie House was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909, and was situated in what was then suburban Chicago. The Robie House is important as a Prairie Style building, as it brings in a sense of nature to an urban area. Where the Reliance building stressed height, the Robie House seemed to spread out across its site, due to the large expanses of horizontal forms. Using both additive and subtractive design, Wright created many of these horizontal forms, increasing the number of faces that the user’s eye would come into contact with. The horizontality of the Robie House also affected its scales; as it did not have to compete with neighboring skyscrapers as the Reliance Building did, and as the use was for a small family unit and not many different kinds and groups of people, the scale is more personal. Horizontality is also expressed through the ornamentation of the exterior; Wright used long, thin bricks and colored mortar to strengthen the sense of the horizontal, as well as group the windows together in bands and cap the forms with concrete.

PEOPLE

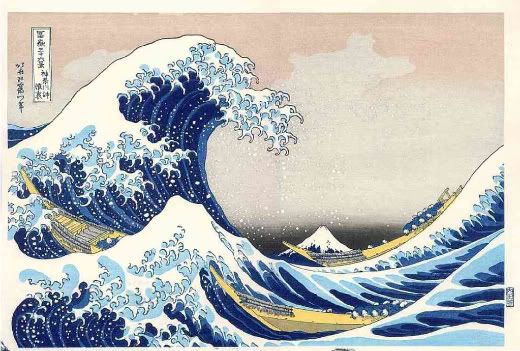

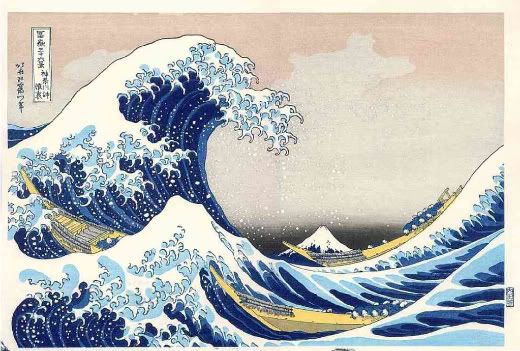

As countries open up their borders for economic opportunities, they trade more than goods and services, but pieces of their culture, which then can be reinterpreted in the culture that receives them. This idea is evident in the 19th century with the rise of Japonisme, which is marked by an influx of Japanese products on the Western scene. People were captivated by new ways these new images, and shifted their meaning and appearance as they assimilated the images into their own culture. These Japanese products introduced a new way of seeing things in their simplicity of form, in the way that line defines shape, muted color palettes, materials, patterns, and thematic devices.

I think this opening up is important as it marks a time when different cultures began to come into contact with each other. The images that a certain culture prescribed to itself became under influence by images from a new culture. Japonisme is not the only response to such events; it is a two way street. As Japan, Korea, China, and other countries opened up, they “modernized”, which is to say they became more Western on the surface. New building types were introduced in Eastern countries as well, which did not really take root until about the turn of the century. But nowadays we are seeing more of a political and cultural shift to these Eastern countries, as we receive more goods and services from them that shape our world today, including products, food, and media.

MATERIAL

During the 19th century we saw a rise in the number of styles, and revivals of styles, all of which had different ways of how they treat the faces, or what their systems of ornamentation are, which is also a key element in understanding how the shifting image relates to the aspects of design. In keeping to a handmade aesthetic, ornamentation is a huge part of telling the story.

The story gets complicated, though, as there is a plurality of choices, but I think what we see throughout the styles is an adherence to the idea of holistic design, that there is a unity in all the arts, and a space exhibits the same qualities throughout all its component parts.

The best example of this idea is the Peacock Room by James McNeill. Colors, materials, forms, lines, shapes… in other words, the elements and principles of design, were all synthesized to create a fluid space. Each part corresponds with the whole, and makes a holistic environment. The walls are even covered in art that correspond to and help set the mood of the space. Another way to put it, I think, is that there is a layering of images going on here. Art would be one image, lighting another, and so on and so forth. The imageability of the space is increased, which aids our understanding and interpretation of it, as these images are matched up in this holistic way of design.

SYMBOL

I think the critical idea here is the rise of the machine and people’s reactions to new technologies. The people of this time period are poised to move from a more reflective view on architecture, relying mainly on past styles [revivals] to a more explorative view on architecture, creating modern spaces [movements]. The main question rotates around the word pairing form-reform: do we continue to make things by hand, or do we use the machine in the process? Styles are born out of this question, either taking on the stance that integrity and authenticity only comes from handmade objects [Arts and Crafts, aesthetic movement, revivals], or responding to and accepting the growth of industry in our everyday lives [Modernism].

Architects Greene and Greene understood this concept well. The Gamble House of Pasadena, California, is a landmark in Arts and Crafts design. It projects a solid image, from macro to micro, through forms, faces, scales, and ornamentation, on all aspect levels. From the technique in which the wood is treated, to how the rooms flow into each other, to how the building incorporates itself with its site, the message remains the same.

I think this same concept is seen throughout the reflections unit, too, this strong inclination towards holistic design to reinforce a message concerning an object’s contexts. It is not limited to one type of design or one region, but can be seen throughout. Designing in terms forms, faces, scales, and ornamentation strengthens the image of an object in all of its layers, creating a more clear imageability for us to experience, interpret, and remember our spaces.

Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press.

The elements that Lynch refer to in his book include paths, edges, districts, and nodes, which describe his city image, but I think can be connected to the world of architecture and the objects people produce, or at least new elements can be invented to illustrate the same sorts of ideas. Lynch defines each element, but then goes on to highlight the importance of the relations between unlike elements, as “such pairs may reinforce one another, resonate so that they enhance each other’s power; or they may conflict and destroy themselves” (pp. 83-84). In other words, there are concrete and abstract relations between elements that shape the image and thus the experience we have of the object. This idea is key throughout the aspects [nature, people, material, symbol], and I will go into greater depth below.

For my purposes, defining a new set of elements would be more apt for the type of objects I will be looking at. I think forms, faces, scales, and ornamentation best describe the sorts of interactions the built environment has with the aspects.

FORMS describes how the object engages (or does not engage) the aspects, as forms create or block off space

FACES describes the surfaces of the forms, which are the visible parts of the forms, and become an interface between the aspects and form

SCALES describes how the aspects relate to the objects, and how the forms and faces of the objects relate to each other

ORNAMENTATION describes how designers mediate between elements, aspects, and objects, and create a dialog that is essentially a snapshot of its contexts

NATURE

The reflections time period is seeing a great shift from rural living to urban living, due to the Industrial Revolution, which shifts a nation’s economy from a primary, or agricultural economy, to a secondary, or industrial economy. There is a huge influx of people into cities, most notably in Europe and America. The key city in the United States at the time was Chicago, which saw a rise in population from 300 in 1833 to 2 million in 1900, even surpassing the population of New York City. Accordingly, as urban areas become dense, the environmental context loses out on a natural site aspect and adopts an architectural site aspect. Chicago demonstrates this idea the best, especially after the Great Fire of 1871, which destroyed an area of Chicago four miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide. With a clean slate, so to speak, and driven by other factors, like higher rates of land price, the advent of a safe elevator, and iron skeletal construction, innovators flocked to Chicago to begin to rebuild. Here we see the birth of the skyscraper.

The skyscraper is important in the development of the American city as it reorganizes the urban center, and in this way the natural site aspect disappears and is replaced by “the concrete jungle”.

The Reliance Building best exemplifies this movement into the urban environment, and its implications are vast and far-reaching. It is a Chicago hallmark, designed with Burnham and Root and constructed between 1883 and 1885. In terms of form, the basic unit that was already defined as the form for the skyscraper is modified; the form is still blocky and heavy, but a geometric undulation is introduced to help break up the space and create more faces. The faces, or the façade, is fluid, and because of careful application of scales and ornamentation we can better understand the relation of the forms to the aspects. There is a strong horizontal feeling, as similar segments are banded together across the faces [windows, ornamented spandrels], which are clearly marked and scaled. It gives us a sense of movement upwards, and the top of the skyscraper stops our eye, like a period at the end of a sentence.

Robie House acts as an interesting foil to the Reliance Building. Another Chicago landmark, Robie House was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909, and was situated in what was then suburban Chicago. The Robie House is important as a Prairie Style building, as it brings in a sense of nature to an urban area. Where the Reliance building stressed height, the Robie House seemed to spread out across its site, due to the large expanses of horizontal forms. Using both additive and subtractive design, Wright created many of these horizontal forms, increasing the number of faces that the user’s eye would come into contact with. The horizontality of the Robie House also affected its scales; as it did not have to compete with neighboring skyscrapers as the Reliance Building did, and as the use was for a small family unit and not many different kinds and groups of people, the scale is more personal. Horizontality is also expressed through the ornamentation of the exterior; Wright used long, thin bricks and colored mortar to strengthen the sense of the horizontal, as well as group the windows together in bands and cap the forms with concrete.

PEOPLE

As countries open up their borders for economic opportunities, they trade more than goods and services, but pieces of their culture, which then can be reinterpreted in the culture that receives them. This idea is evident in the 19th century with the rise of Japonisme, which is marked by an influx of Japanese products on the Western scene. People were captivated by new ways these new images, and shifted their meaning and appearance as they assimilated the images into their own culture. These Japanese products introduced a new way of seeing things in their simplicity of form, in the way that line defines shape, muted color palettes, materials, patterns, and thematic devices.

I think this opening up is important as it marks a time when different cultures began to come into contact with each other. The images that a certain culture prescribed to itself became under influence by images from a new culture. Japonisme is not the only response to such events; it is a two way street. As Japan, Korea, China, and other countries opened up, they “modernized”, which is to say they became more Western on the surface. New building types were introduced in Eastern countries as well, which did not really take root until about the turn of the century. But nowadays we are seeing more of a political and cultural shift to these Eastern countries, as we receive more goods and services from them that shape our world today, including products, food, and media.

MATERIAL

During the 19th century we saw a rise in the number of styles, and revivals of styles, all of which had different ways of how they treat the faces, or what their systems of ornamentation are, which is also a key element in understanding how the shifting image relates to the aspects of design. In keeping to a handmade aesthetic, ornamentation is a huge part of telling the story.

”The right question to ask, respecting all ornament, is simply this: was it done with enjoyment?”John Ruskin, Seven Lamps of Architecture

The story gets complicated, though, as there is a plurality of choices, but I think what we see throughout the styles is an adherence to the idea of holistic design, that there is a unity in all the arts, and a space exhibits the same qualities throughout all its component parts.

The best example of this idea is the Peacock Room by James McNeill. Colors, materials, forms, lines, shapes… in other words, the elements and principles of design, were all synthesized to create a fluid space. Each part corresponds with the whole, and makes a holistic environment. The walls are even covered in art that correspond to and help set the mood of the space. Another way to put it, I think, is that there is a layering of images going on here. Art would be one image, lighting another, and so on and so forth. The imageability of the space is increased, which aids our understanding and interpretation of it, as these images are matched up in this holistic way of design.

SYMBOL

I think the critical idea here is the rise of the machine and people’s reactions to new technologies. The people of this time period are poised to move from a more reflective view on architecture, relying mainly on past styles [revivals] to a more explorative view on architecture, creating modern spaces [movements]. The main question rotates around the word pairing form-reform: do we continue to make things by hand, or do we use the machine in the process? Styles are born out of this question, either taking on the stance that integrity and authenticity only comes from handmade objects [Arts and Crafts, aesthetic movement, revivals], or responding to and accepting the growth of industry in our everyday lives [Modernism].

Architects Greene and Greene understood this concept well. The Gamble House of Pasadena, California, is a landmark in Arts and Crafts design. It projects a solid image, from macro to micro, through forms, faces, scales, and ornamentation, on all aspect levels. From the technique in which the wood is treated, to how the rooms flow into each other, to how the building incorporates itself with its site, the message remains the same.

I think this same concept is seen throughout the reflections unit, too, this strong inclination towards holistic design to reinforce a message concerning an object’s contexts. It is not limited to one type of design or one region, but can be seen throughout. Designing in terms forms, faces, scales, and ornamentation strengthens the image of an object in all of its layers, creating a more clear imageability for us to experience, interpret, and remember our spaces.

Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home