☆ 018 ; alternatives: the shifting image

Previously I had defined "the shifting image" as a set of images that are overlapped and interrelated that vary on scale from the micro [a detail such as the door handle and how it fits in your hand] to the macro [how the building fits in its contexts, such as how it responds to the building around it]. Now I want to layer another piece on top of that definition, and that's the idea of imageability. Kevin Lynch, author of The Image of the City, who developed the original idea of the shifting image, defines imageability as" the quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer" (p. 9). Imageability refers to perceptual learning and how we receive, interpret, and store information that we come into contact with through our senses. It's about the hidden forms and scales. After all, architecture, according to Suzanne Langer, "is the total environment made visible" (Lynch, p. 13). In this way, architects are the people who gather information about the many contexts before the building is even designed, and boils all the information down then translates into building form. Thus, the building form relies heavily upon its culture, which informs designers what is acceptable and what is not, availability of materials and the sense it makes to use them, site conditions [including weather, sun patterns, topography, demography, etc], and precedents.

Questions that arise as a result of integrating imageability into the definition:

NATURE

To answer my first question about which layers does nature occupy, it seems to occupy a small amount, or, at least, less significant ones, but this is always subject to fluctuation. I think in the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque time periods, we see a movement into the city, but then a movement back out. As people urbanized, they get used to being surrounded by a built environment. They might even develop a preference to being in the city. I remember a fourth year, who studied abroad in Italy, saying Italians much rather stand on concrete than stand in grass. Nature then becomes a commodity, and one goes to the country to get away from it all. It's a familiar concept, as it's something we do in our society today.

I think this movement starts in Italy, the best model [that is, the object that evokes the strongest image] being the Villa Capra by Palladio [photo 1, below]. The villa was the rural counterpart of the palazzo in urban Italy. The Villa Capra dominates its landscape, and offers views while also making views with the four-porch façade. I think it recalls the ziggurat form that we see in early Mesopotamia, the artificial mountain that rises from the sands to call out to people from all directions. There begins to be a stronger tie to the landscape later in Italy, as we see with the Medici palace where places are designed in the gardens for socialization and activity. The natural environment then becomes an extension of the built environment; one is not just standing anywhere, one is standing somewhere.

This idea of the landscape being a part of the built environment then moves to France, where it's taken to the extreme, as seen at the Palace of Versailles [photo 2, below]. As I mentioned in a previous entry, Paris [and then Versailles] is the definition of France as a primate city, which became that way through the king exercising his power in the absolute monarchy. This idea manifests itself through the design of the gardens at Versailles. I think it's important to note that the views you get in current photographs aren't the same views as they were during its height: the trees that line the natural avenues that cut through the gardens would've been carefully shaped into box forms. The straight lines, carved trees, and control of water are all indicators of the king's one power, which was such that he could conquer nature.

The shaped landscape also takes root in England [photo 3, below], but in a different manner from both Italy and France. Called the picturesque, which also became a popular painting style, the English gardens were made to look as they would in nature, that is, undisturbed and free, but were actually planned to look that way. The best possible image was selected and viewpoints were planted throughout the gardens as little Classical structures, where the person could stand and always see a beautiful scene.

Overall, though, I believe that the layers of the actual built environment [the villas, the palaces, the country houses] dominated the images of the natural environment. The structures spread out and captured as much as the view as possible, as such is the case in the sprawling Palace of Versailles, or by extending upward.

There's a direct translation of this general image into our society. People like to spend time outdoors without the mess, so we see the development of areas affixed to houses, such as decks or pool areas, and then more public spaces such as arboretums, lawns at universities, and playgrounds.

→

PEOPLE

People work within layers of verbs in their environments: living, working, socializing, worshipping, to name a few. These verbs get translated into the built environment through levels of functions: a house is for living, an office is for working, a house could also be for socializing, a church is for worshipping, and so forth. Where these functions overlap, such as the living and socializing in the house, there are distinctions between functions. Public and private are filtered into areas, like in the palazzo, where work and socialization would happen on lower floors, and upper floors were reserved for the family. In terms of worship, I immediately think of Ste. Chapelle, where the lower arcade area was split from the upper triforium and clerestory, the lower for commoner worship and the upper for the king's worship.

This idea also works on the scale of civic to private spaces. St. Peter's Cathedral best exemplifies this idea; there is a large public space before the actual cathedral that serves as a space for the masses to gather during events to hear the Pope. When the user moves inside [perhaps for worship purposes, but I can't ignore the fact that tons of tourists move through the space, too, with a different lens of seeing the space], the function of the space becomes more personal. While the main interior is large in scale, there are areas that bring the scale down, particularly the baldacchino, which brings the focus to the center.

MATERIAL

Material is all about evoking a strong image in the viewer, as it is the most immediate layer, the layer of contact and of the senses. You can feel stone, you can see color and light, you can hear the echoes off the walls. It's the interface, so I think it's the most important. Material takes on different properties throughout the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque time periods. I also think you begin to see light as a material, which indicates that designers are beginning to think more about the site and how best to take advantage of the sun.

In the Gothic era, stone as a material was important. On the exterior, the cathedrals may look heavy, clunky almost, and this is certainly due to the buttresses, but those exist as a support system as it is moved from the interior to the exterior. The interior then becomes about the stretching of stone, those thin columns extending into the heavens. The point was to make stone look as light as possible.

Another reason why the main structures were moved to the outside of the cathedrals were to afford more space for the stained glass windows that are basically the skins of the building. The windows became an important tool as ways to communicate with the masses, who were generally illiterate. They contained Biblical images and lessons. They tie back to faith and memory; the strong image evoked here makes a deep impression in the minds of the architecturally literate [which they all were, people were much better at reading spaces in previous times than they are now], and certain ideas and feelings are then attached to these spaces-- epiphany, fear, awe, perhaps.

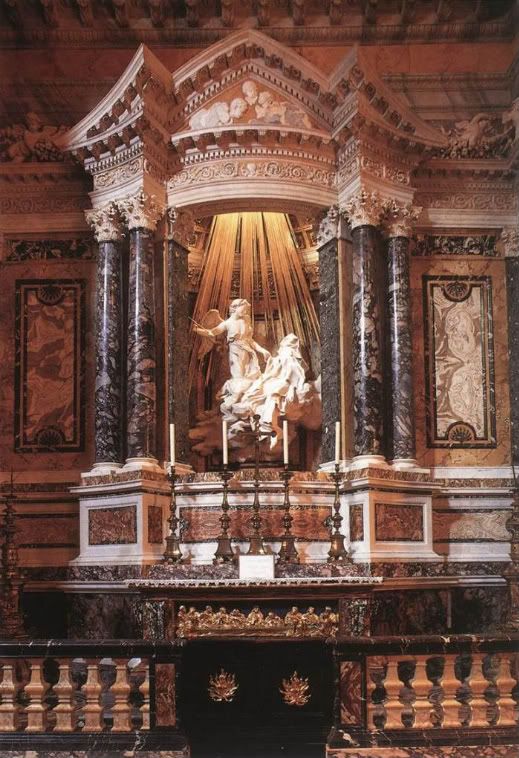

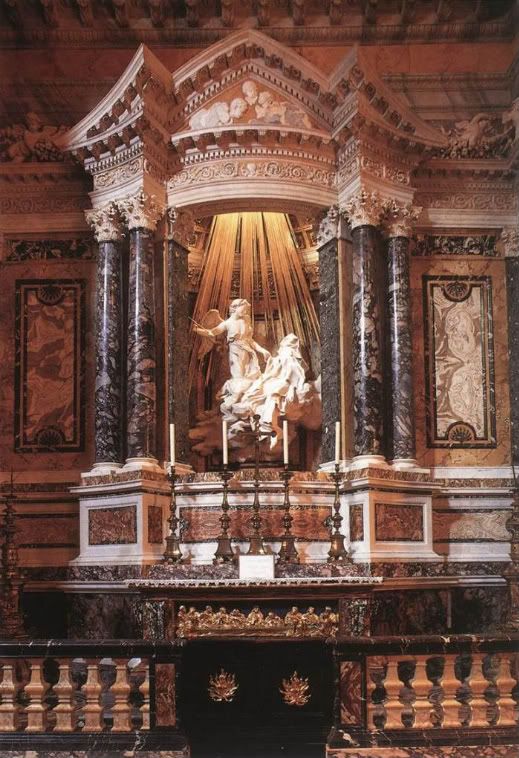

In the Baroque era, material took on a new meaning. Baroque materials were sumptuous, rich, overwhelming. The best example of this would be Bernini's Ecstasy of St. Theresa; the different colored marbles combined with the carved image of St. Theresa resting on clouds and the gold "light" that filters down from the heavens creates such a sense of place, it's singular, unique, a strong treatise on faith and the Baroque.

SYMBOL

Here I think the question What do these layers say about the society who constructed them? is most important. I thought of many word groupings that could be applied, including religion/god/faith, interior/exterior, urban/rural, and defining rules/breaking rules, all of which reference ideas already outlined above.

In terms of religion, symbols were used in Gothic cathedrals to tell the masses of the Bible. Every surface became a blank canvas for artisans to write upon, and no surface was left untouched. As seen in class, even the capitals on columns were carved with figures, showing scenes from the Bible. We see this as well on the stained glass windows. The scale of these cathedrals, which towered over the rest of the city in which they resided, speaks to the fact that religion was the key institution during this time period.

Interior and exterior boundaries are beginning to be blurred throughout the eras mentioned in this alternatives unit, particularly in the gardens that served as outdoor interior spaces. Gardens became symbols of the king's power, as was the case at Versailles, or served entertainment purposes, as they did in Italy. The urban/rural duality ties in with the idea of interior/exterior, too. The villa form in Italy, for example, was like a palazzo, except in an urban context. Countryside retreats were about exactly that, retreating from the city.

Finally, there's this important idea of defining rules versus breaking rules, which references the design cycle. Certainly there were rules during the Gothic period, which were vastly different rules than during previous periods. But the rules didn't become so important again until the Renaissance, when we saw a rebirth of Classical ideas. As there was very little written about the built environment during the Classical period, though, I think Renaissance designers had much greater latitude to interpret the evidence to suit their needs and contexts. People then began to codify these rules, and there arose certain expectations for building types to look a certain way. Mannerist designers began to break these rules; my favorite example of this would be Michelangelo's Laurentian Library stairs. The surrounding envelope of the space contained Classical elements, but with a twist, such as the columns that were embedded into a space carved out specifically for them, instead of being surface treatments as pilasters. The Baroque operated within the same sets of rules as the Renaissance, but broke them, perhaps as statements of originality or commentary and reflections on themselves.

CLASSICAL → GOTHIC → RENAISSANCE → MANNERISM → BAROQUE

Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press.

-----

On a side note, Stephanie, who has been my BFF throughout this whole iarc gig, sent me some photos, and this one in particular made me lol:

For awhile I was on the lam, apparently not paying University Graphics & Printing for a print job! I blame this on a club I was with back in the day, but it's still hilarious to think I was a fugitive. It eventually caught up with me in a dramatic, tearful fashion, but that's another story.

Also, my favorite band, Epik High dropped their album. If I could spread the word and just get one more person into them and buying their album I'd feel quite accomplished. Visit their website here, and below is the video from their first single, Map the Soul. They also have an English language version of this song, which is freaking amazing! Such great lyrics. &hearts

Questions that arise as a result of integrating imageability into the definition:

Which layers does/do [nature/people/material/symbol] occupy?

How are these layers synthesized?

What do these layers say about the society who constructed them?

Which objects evoke a strong image?

NATURE

To answer my first question about which layers does nature occupy, it seems to occupy a small amount, or, at least, less significant ones, but this is always subject to fluctuation. I think in the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque time periods, we see a movement into the city, but then a movement back out. As people urbanized, they get used to being surrounded by a built environment. They might even develop a preference to being in the city. I remember a fourth year, who studied abroad in Italy, saying Italians much rather stand on concrete than stand in grass. Nature then becomes a commodity, and one goes to the country to get away from it all. It's a familiar concept, as it's something we do in our society today.

I think this movement starts in Italy, the best model [that is, the object that evokes the strongest image] being the Villa Capra by Palladio [photo 1, below]. The villa was the rural counterpart of the palazzo in urban Italy. The Villa Capra dominates its landscape, and offers views while also making views with the four-porch façade. I think it recalls the ziggurat form that we see in early Mesopotamia, the artificial mountain that rises from the sands to call out to people from all directions. There begins to be a stronger tie to the landscape later in Italy, as we see with the Medici palace where places are designed in the gardens for socialization and activity. The natural environment then becomes an extension of the built environment; one is not just standing anywhere, one is standing somewhere.

This idea of the landscape being a part of the built environment then moves to France, where it's taken to the extreme, as seen at the Palace of Versailles [photo 2, below]. As I mentioned in a previous entry, Paris [and then Versailles] is the definition of France as a primate city, which became that way through the king exercising his power in the absolute monarchy. This idea manifests itself through the design of the gardens at Versailles. I think it's important to note that the views you get in current photographs aren't the same views as they were during its height: the trees that line the natural avenues that cut through the gardens would've been carefully shaped into box forms. The straight lines, carved trees, and control of water are all indicators of the king's one power, which was such that he could conquer nature.

The shaped landscape also takes root in England [photo 3, below], but in a different manner from both Italy and France. Called the picturesque, which also became a popular painting style, the English gardens were made to look as they would in nature, that is, undisturbed and free, but were actually planned to look that way. The best possible image was selected and viewpoints were planted throughout the gardens as little Classical structures, where the person could stand and always see a beautiful scene.

Overall, though, I believe that the layers of the actual built environment [the villas, the palaces, the country houses] dominated the images of the natural environment. The structures spread out and captured as much as the view as possible, as such is the case in the sprawling Palace of Versailles, or by extending upward.

There's a direct translation of this general image into our society. People like to spend time outdoors without the mess, so we see the development of areas affixed to houses, such as decks or pool areas, and then more public spaces such as arboretums, lawns at universities, and playgrounds.

→

PEOPLE

People work within layers of verbs in their environments: living, working, socializing, worshipping, to name a few. These verbs get translated into the built environment through levels of functions: a house is for living, an office is for working, a house could also be for socializing, a church is for worshipping, and so forth. Where these functions overlap, such as the living and socializing in the house, there are distinctions between functions. Public and private are filtered into areas, like in the palazzo, where work and socialization would happen on lower floors, and upper floors were reserved for the family. In terms of worship, I immediately think of Ste. Chapelle, where the lower arcade area was split from the upper triforium and clerestory, the lower for commoner worship and the upper for the king's worship.

This idea also works on the scale of civic to private spaces. St. Peter's Cathedral best exemplifies this idea; there is a large public space before the actual cathedral that serves as a space for the masses to gather during events to hear the Pope. When the user moves inside [perhaps for worship purposes, but I can't ignore the fact that tons of tourists move through the space, too, with a different lens of seeing the space], the function of the space becomes more personal. While the main interior is large in scale, there are areas that bring the scale down, particularly the baldacchino, which brings the focus to the center.

MATERIAL

Material is all about evoking a strong image in the viewer, as it is the most immediate layer, the layer of contact and of the senses. You can feel stone, you can see color and light, you can hear the echoes off the walls. It's the interface, so I think it's the most important. Material takes on different properties throughout the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque time periods. I also think you begin to see light as a material, which indicates that designers are beginning to think more about the site and how best to take advantage of the sun.

In the Gothic era, stone as a material was important. On the exterior, the cathedrals may look heavy, clunky almost, and this is certainly due to the buttresses, but those exist as a support system as it is moved from the interior to the exterior. The interior then becomes about the stretching of stone, those thin columns extending into the heavens. The point was to make stone look as light as possible.

Another reason why the main structures were moved to the outside of the cathedrals were to afford more space for the stained glass windows that are basically the skins of the building. The windows became an important tool as ways to communicate with the masses, who were generally illiterate. They contained Biblical images and lessons. They tie back to faith and memory; the strong image evoked here makes a deep impression in the minds of the architecturally literate [which they all were, people were much better at reading spaces in previous times than they are now], and certain ideas and feelings are then attached to these spaces-- epiphany, fear, awe, perhaps.

In the Baroque era, material took on a new meaning. Baroque materials were sumptuous, rich, overwhelming. The best example of this would be Bernini's Ecstasy of St. Theresa; the different colored marbles combined with the carved image of St. Theresa resting on clouds and the gold "light" that filters down from the heavens creates such a sense of place, it's singular, unique, a strong treatise on faith and the Baroque.

SYMBOL

Here I think the question What do these layers say about the society who constructed them? is most important. I thought of many word groupings that could be applied, including religion/god/faith, interior/exterior, urban/rural, and defining rules/breaking rules, all of which reference ideas already outlined above.

In terms of religion, symbols were used in Gothic cathedrals to tell the masses of the Bible. Every surface became a blank canvas for artisans to write upon, and no surface was left untouched. As seen in class, even the capitals on columns were carved with figures, showing scenes from the Bible. We see this as well on the stained glass windows. The scale of these cathedrals, which towered over the rest of the city in which they resided, speaks to the fact that religion was the key institution during this time period.

Interior and exterior boundaries are beginning to be blurred throughout the eras mentioned in this alternatives unit, particularly in the gardens that served as outdoor interior spaces. Gardens became symbols of the king's power, as was the case at Versailles, or served entertainment purposes, as they did in Italy. The urban/rural duality ties in with the idea of interior/exterior, too. The villa form in Italy, for example, was like a palazzo, except in an urban context. Countryside retreats were about exactly that, retreating from the city.

Finally, there's this important idea of defining rules versus breaking rules, which references the design cycle. Certainly there were rules during the Gothic period, which were vastly different rules than during previous periods. But the rules didn't become so important again until the Renaissance, when we saw a rebirth of Classical ideas. As there was very little written about the built environment during the Classical period, though, I think Renaissance designers had much greater latitude to interpret the evidence to suit their needs and contexts. People then began to codify these rules, and there arose certain expectations for building types to look a certain way. Mannerist designers began to break these rules; my favorite example of this would be Michelangelo's Laurentian Library stairs. The surrounding envelope of the space contained Classical elements, but with a twist, such as the columns that were embedded into a space carved out specifically for them, instead of being surface treatments as pilasters. The Baroque operated within the same sets of rules as the Renaissance, but broke them, perhaps as statements of originality or commentary and reflections on themselves.

Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press.

-----

On a side note, Stephanie, who has been my BFF throughout this whole iarc gig, sent me some photos, and this one in particular made me lol:

For awhile I was on the lam, apparently not paying University Graphics & Printing for a print job! I blame this on a club I was with back in the day, but it's still hilarious to think I was a fugitive. It eventually caught up with me in a dramatic, tearful fashion, but that's another story.

Also, my favorite band, Epik High dropped their album. If I could spread the word and just get one more person into them and buying their album I'd feel quite accomplished. Visit their website here, and below is the video from their first single, Map the Soul. They also have an English language version of this song, which is freaking amazing! Such great lyrics. &hearts

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home