☆ 013 ; foundations: the shifting image

The phrase “the shifting image” conjures up many, well, images in my mind. Using what Kevin Lynch had to write about it in his book The Image of the City as framework, I was able to create a working definition of the phrase. The shifting image is not a single image, yet a set of images that are overlapped and interrelated, much like the above panoramic image I stitched together. These images can be arranged on many different levels according to scale, moving from macro to micro, outward to inward, which then make up one grand image. We are not able to experience [see, feel, smell, hear, etc] all of the image at once, but can gain a sense of place through experiencing sequences of images, which we connect together in our minds to create something larger. The levels include nature-related aspects, such as time of day, season, and weather, and human-related aspects, such as viewpoint, and “secular shifts in the physical reality” (Lynch, p. 86) relating to human-controlled physical aspects of the site, such as landscaping or auxiliary spaces, like the placement of sidewalks. Layered on top of that, I think, are social, political, and historical contexts that pull on the design cycle model; the way a person is conditioned to think and what is happening around that person at a certain point in time certainly affects the perception of the image.

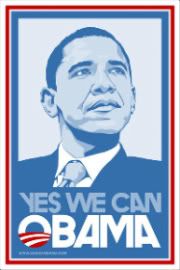

I think a good way to explain it visually is with a variety of Obama graphics stating the same written message, yes we can. Imagine one of these graphics fixed to a wall of a building outside. In terms of scale, this little bit of information gets lost as we move outward and out of view, but as we turn the corner, spot it, and walk towards it, it changes. It changes in actual size, due to perspective, and in color depending on where we are standing in relation to the light. Speaking of lighting, the image changes depending on the time of day, between the softer lights of the morning and evenings and the stronger lights of the afternoon. Light is key to color and the ability to see; if it was dark outside, we may just pass this poster without seeing it. As we pass it and leave it behind, we don’t physically see it anymore, but there’s an imprint of the information in our minds. Other contexts affect how we see the image, but on a more personal level. If one was a die-hard conservative, certain emotions might be inflamed upon seeing this image. The opposite is true as well; if one agrees with Obama’s platforms and policies, then the image would conjure up positive feelings and thoughts. The fact that he is the first black man in such a high position is also indicative of the sociopolitical image and reflects our history as Americans. But as the poster is left up it begins to tear, rain and sun washing out the colors, and soon it peels off the wall. Someone picks it up and puts it in the trash, leaving only a residue of the image in our minds.

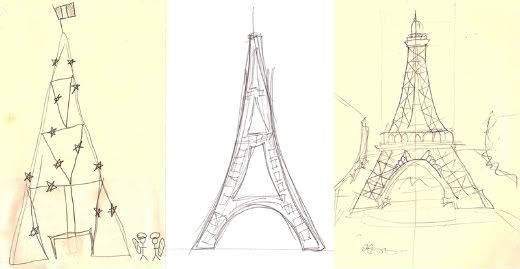

Another point I’d like to bring up in regards to the shifting image and as displayed by the Obama graphics above are the ideas of simplification and continuity. We can all recall what the image looks like after seeing it a few times (whether it’s an actual image like the above or a city, like Paris or Seoul), but once we sit down and try to make representations of that image details on several levels of scale begin to get lost. If one is working on the level of a graphic, color and lines can be translated in different ways, as evidenced by the Obama graphics. The man and his values are still the idea, but each image is different. On the other hand, if I were to draw the Eiffel Tower from memory, it would definitely be more of a gesture of the place, and I could never go into detail about the form or the surrounding areas without references.

The above drawings are two representations of the Eiffel Tower done from memory, one by my boyfriend, Jason, who has very little architectural experience but has been to the site (which features the two of us in the corner with larger-than-life baguettes!), one by my friend Stephanie, another fifth year who has not been to the site, and one by myself. The point I’m trying to make here is about continuity: after simplifying an image, there are different ways to represent the image, and though they may be different they are continuous in that they pull down from one overarching idea, they highlight what it is that people see and what is important. Students do this everyday as they sketch from slides or from real life; they note the main points and capture the essence.

Now that I have a definition for “the shifting image” I can now apply it to what we’ve learned in the foundations unit. I will go about this section by talking about each aspect, then objects will be defined within each aspect. Objects may not be the same across each aspect, as I will pick the ones that best represent the material.

NATURE

First of all, the aspect of nature clearly calls upon the parts of the definition of “the shifting image” that is about time of day, season, and weather. These parts of the aspect are parts that we cannot control, but to which we can respond. Generally, the responses can be made in one of two ways: we can take the site into consideration, like the Greeks, or ignore it, like the Romans.

The best example of this difference is the theater of Dionysus, a Greek structure, and the Colosseum, a Roman structure. Both have the same aim as entertainment centers, but such is the difference between the two that they merit different names: the theater and the amphitheater. The Greek theater takes advantage of the landscape, being built into it, and creates a sense of place and a more solid image of itself. On the other hand, the Colosseum, an amphitheater, rises out of an urban context, no scale of nature in proximity to its form. These images are different in the natural context, and flow differently as a result as people move about them.

Both forms lend themselves to translation throughout space and time. Above is the theater at Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea, and the Greenbsoro Coliseum here in town. The parallels between the two pairs, the Yonsei theater/the theater of Dionysus and the Colosseum/the Greensboro Coliseum, are quite clear: like the theater of Dionysus, the Yonsei theater is built into a slope and surrounded by natural objects, such as trees, but the Greensboro Coliseum, like the Colosseum in Rome, is a free-standing structure that dominates that area, which happens to be urban in its context.

Time of day and weather also relate to the natural image of all of these sites. Time of day not only dictates the kind of light that surrounds the area, but also what sort of function the space takes on. Big concerts and other such events at the Greensboro Coliseum usually take place in the evening, so it lends itself to how we experience that space and understand it once we step away. Likewise, at the Yonsei theater, during the morning and day I’ve seen sports clubs using the space as practice, running up and down the stairs, but concerts and other school events are also held there. In this way, one space shifts within its image to become different spaces to different user groups.

Weather is a key factor as well. Open spaces like the Colosseum in Rome were able to be designed and built because of the climate; the warm climate of Italy allows for more open structures, and could be used more often. The same place could not exist in a cold or rainy environment without some design alterations taken, and even on a rainy day in Rome the Colosseum would not be the same.

PEOPLE

People are an important part of “the shifting image” as well, as they add a physical scale and a personal scale to the built environment. Objects, such as the Column of Trajan, can be monumental in physical scale, and extremely significant in terms of Rome’s history on a personal scale, whereas the pilaster, a borrowed column form in Rome, occupies a smaller and less important niche in architectural language, both physically and personally.

Places, for the most part, are built for people. Some are built for gods, some are built for the pure delight aspect, but most have commodity and firmness. The best example of a shifting image in terms of personal perspective is that of the Acropolis in Athens. Every four years the people of Athens would hold a special procession to the top of the Acropolis. The key term here is procession, which implies a point A, a journey, and a point B (possibly a point C, D, and so on, as well). Here the image shifts as a person moves, a new view given at each turn, which is highlighted in the passage up from the town and into the Acropolis. The view moves from macro to micro, from the overall view of the Acropolis, up through the Propylaea (which guides the person and gives them bits of information about what they are about to view), the first view of the Parthenon, and then to the details, such as the frieze (which depicts the Procession, and we come full circle).

Imagine it this way: as you’re making this journey, you take a picture every ten steps of what’s directly in front of you. Layer these images, and that’s the shifting image.

MATERIAL

Across the board, from Mesopotamia to Rome, stone was used as a material. Mockups, such as the wooden one from Stonehenge, only served as a practice run, a sketch of the image. Stone (and later concrete, in Roman times) is a mostly-permanent material (as we see these buildings in ruin now), but even then that’s about the image. These structures as wholes mean something different than these structures in pieces. If it was about permanence then, it’s about age and timelessness now. In America, particularly, we borrow upon this image to make our own, as evidenced by governmental and financial institutions, such as the Capitol. The meaning shifts along with it to form a new idea and give identity, suggesting the permanence and strength of such institutions.

SYMBOL

Symbol, I think, ties in with nature, people, and material. As I said above for materials, a certain material can suggest an idea, such as timelessness or strength, as is the case in Egypt where pyramids made of stone were meant to last for eternity, since the pyramids were tombs for the godlike pharaohs. This use of materials is indicative of a society’s values, religious or not, like the idea of the afterlife being more important than life on Earth in Egypt.

In terms of people, we can learn from the Column of Trajan and triumphal arches, which tell stories about the people to whom they’re dedicated. The Column of Trajan depicts, in scroll-like fashion, the conquests of the Emperor Trajan, and becomes a sort of history book for the people of the Roman Empire. Another example of this writing upon architectural structures would be the triumphal arch, which carries on throughout history. The most famous arch occurs outside the foundations unit timeline in Paris at the convergence of boulevards and the Champs Elysées: l’Arc de Triomphe, which is dedicated to Napoleon. The same idea of telling a history exists there as well, but most interestingly, concerning both, I wonder if it’s a true history. I think that idea would be a part of the shifting image—you have the true history, and the history that’s recorded architecturally, and there might be discrepancies between the two. Also, an event as its known twenty years out from its point of occurrence, to 100 years out, to 1,000 years out, changes as the society moves from social form to social form, as shaped by technology. Hindsight is always 20/20, they say!

In the natural sense of the symbol, it can be argued that the first columns were based off of plant forms, such as the columns we see in Egypt. But I think this idea is more strongly represented in later styles, especially the Art Nouveau movement.

Symbol can also lead to other phrases or ideas that are culturally embedded. On the surface, their significance may be light, but as we move deeper the true meaning becomes apparent. Let’s take the phrase “all roads lead to Rome”. This phrase obviously implies the importance of Rome as a social, cultural, and political center for the empire, but it’s also literally true. These roads were also straight, which feeds into the aspect of nature; Romans ignored the topography of the land in favor of a sense of order according to geometry. We can also see this idea in action with the aqueducts.

Lastly, about symbols, I’d like to point out this idea of visual literacy. It’s no surprise that written and pictorial histories were applied to the surfaces of structures throughout the foundations period, from hieroglyphics in Egypt to friezes in Greece to triumphal arches in Rome. An image is applied, whose meaning is embedded within the society that created it, and we are left to use our knowledge of design, which includes examining the contexts, to interpret the meaning and applying the lessons to our own work, thus shifting the image.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home